Medical Emergency at Sea

Dutch sailors Peter Hoefnagels and Inge van Berkel are sailing around the world without using fossil fuels on board their yawl-rigged sustainable yacht The Ya. Peter has already completed one circumnavigation aboard The Ya (2016 – 2018), which is now on her second trip around the world having left the Netherlands in 2020. Peter and Inge were heading for the Marquesas in French Polynesia when disaster struck.

Murphy’s Law – Double-Handed to Solo Sailing Mid-Pacific

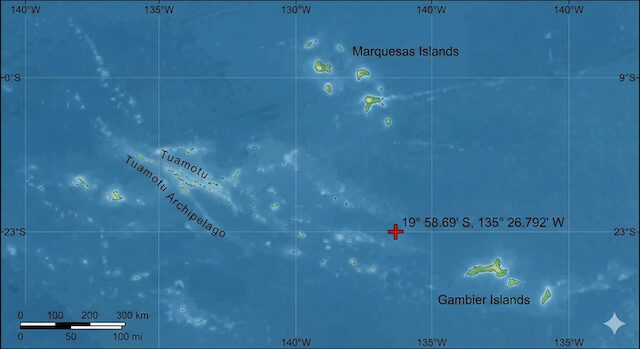

We had already been at sea for a week since our departure from the Iles Gambier and were thoroughly enjoying the calm, steady southeast trade winds. We had left the Tuamotu Islands on our port tack and were heading for the Marquesas. This French Polynesian archipelago is somewhat remote in the north of the South Pacific. Remote – that’s what we want. We were on a course of 350 degrees.

During the night, the wind shifted to the northeast – just too much to allow the jib to be set – so at 07:00, during the changing of the watch, I furled the sail. The halyard slipped briefly and just then a wave collided with our boat – the Ya – causing me to slide. I fell back onto the edge of the cockpit seat. A searing pain.

I breathed in and out, stood up very calmly, and tried to pull the halyard again, but again that pain paralyzed everything. Feeling a little dizzy, I hold on to the pole in the cockpit and slowly lower myself. I crawl inside on my hands and knees. I suddenly need to use the restroom. From there, I find the nearest berth, the “peake” berth.

I’m out of commission. Inge (my wife) takes over. We’re then 250 miles from the nearest island in the Marquesas. That’s Fatu Hiva, one of the (even) more remote islands in the Marquesas. I briefly considered sailing to a Tuamotu island. But that’s actually just as remote. And, in case I would get a bit better, from Fatu Hiva it is only 160 miles to Nuku Hiva where there is a little hospital.

Yet, even now, we unexpectedly have to sail close to the wind. Despite all the weather models, we deal with a northerly wind. I’m lying in the berth, tossing and turning, in constant pain. Inge and I agree it’s a broken or bruised rib. Inge had once bruised a few ribs herself and recognizes the symptoms. It’s probably bruised, because that’s what hurts the most and Inge doesn’t see or feel any irregularities on my back.

Inge is now doing everything: cooking, navigating, sailing… I’m in so much pain that my care is limited to giving me ibuprofen with water, which I drink through a straw. I take the maximum of 3 grams for the first few days. Every now and then, I get an unexpected stabbing pain, as if someone is spraying boiling water on my back. Only the next day I am bright enough to ask Inge to bear down for a while, so I can find a better berth. I slowly slide out of the berth and manoeuver as carefully as possible to the cabin.

An hour later, I’m lying in the pilot berth, midships, and it’s much calmer there. I can only lie on my stomach, but it’s a blessing. I discover I can sit-lie on my knees. Inge can now slide a bedpan under me (a clever trick involving a large bottle cut open and my penis fits in).

From then on, Inge really gets busy. Taking care of me takes up quite a bit of time. The wind—even against the latest forecasts—continues to come from the north and is increasing. It’s necessary to lower the furled outer jib anyway, because it makes a difference of 5-10 degrees upwind. Normally, you do that with two people, but Inge—five feet tall and 60 kilos—does it smoothly on her own on the foredeck and without risk for her own safety. She also double-reefs the mainsail. I normally do that, but she simply takes a photo and asks, “Is that right?” and forty-five minutes later, the reef is perfectly in place.

Then the pain subsides somewhat. Until I cough: that same searing pain again, like cooking water on that particular place on my back, and it is lasting a minute. For us another confirmation that it must be the ribs. But we remain cautious; I do everything lying down and only move for eating and peeing. Inge uses the blender in all my food and pours it into a mug, which I suck down through a straw.

Anchoring with Murphy – 1

Two and a half days later, we arrive in the lee of Fatu Hiva. Inge lowers the sails as soon as the sea is calm behind the island. I have to leave my bunk now and with 3 grams of ibuprofen and 2 grams of paracetamol, I manage to make the two-meter and two-step walk from the pilot berth to the cockpit in half an hour. Inge can’t do the manoeuvering alone. It’s a new moon, and the clouds above the high island block even the meagre starlight. It’s pitch black, and we’re completely dependent on the radar. I can read and operate it. And that’s necessary, because the bay turns out to be completely full. That’s bad luck too.

We try to anchor as close to shore as we can, at the 10-meter depth line. From there, the pilot book says, there’s sand. We anchor 40 meters in front of a yacht. It almost never happens, but the anchor seems to be dragging. “It’s like we’re dragging a whole cemetery,” says Inge. She hauls in the anchor… until the windlass motor stops pulling. There’s something attached to the anchor that weighs a lot. At least 100 kilos. A crab crate? A piece of oddly shaped coral?

I steer as best I can back towards the shallows, dragging the thing along the bottom. Unfortunately, it won’t let go of the anchor. At 7.5 meters deep, the bottom offers more resistance, possibly a bit rocky or coral, so I stop and with some slack, Inge reels in the chain as far as possible.

Anchoring with Murphy – 2

With the thing still hanging off the bow with 7.5 meters of chain, I maneuver very slowly sideways, taking advantage of the leeway, calmly passing between the anchored boats. Meanwhile, Inge retrieves the second anchor from the locker and prepares it on the stern. It’s a large aluminium Fortress anchor without chain, but with a lead line. We now anchor behind all the boats, in a spot where – according to the chart – there’s sand. It’s 25 meters deep there, so Inge ties the anchor to our 200-meter line. Without a chain, we first add 150 meters of line to be absolutely sure. The bay is known for its gusty winds and the line needs to stretch completely. The anchor held well at this point. We were happy. After three hours on my feet, I went to bed.

The night with Murphy

Every boat makes some degrees to left and right behind its anchor. With that long line, the distance can become quite a lot. This became clear when Inge woke me at four in the morning: “Peter, we’re close to shore. I can see the waves breaking on the black rocks at the bottom of the cliff.”

Or has the wind shifted a bit? One thing’s for sure: we’re moving pretty much to the left and the right behind the anchor. At night you can’t judge distance, but the shore seems close. Especially when it is very dark, and the white foam is illuminating between the black rocks. But what protects us is the anchor with the “thing” on it, hanging off the chain at 7.5 meters. If it touches the bottom, it stops the swing. Or should we re-anchor? That’s unwise in the middle of the night. I really have to stay flat and Inge is tired; that’s how you make mistakes. I weigh up the high risk of making mistakes against the small risk of hitting a rock (and then sailing away) and decided to stay put and only shorten the anchor line by 20 meters. That will reduce the swing a bit, and we can sleep for our much-needed rest.

The day with Murphy

In the morning, the wind shifts slightly. Strong gusts are also coming into the bay. The Ya sometimes creeps quite close to the jagged rocks. What now? I have to stay in bed; Inge isn’t fully rested yet – and she’s quite busy anyway. Also, the anchor battery appears to be weak from the heavy loads during the night; it might even be broken.

First, calm on board and a fresh crew. In daylight, we can accurately estimate the distance to the rocks: it turns out to be about 30-40 meters. And—one of the advantages of electric motors—we can sail away in seconds if we want. We’ve set the stern anchor with the line on the port side, so with the port propeller, we can turn away from the cliff and into the depths.

Now for the battery. I have a spare, but I don’t see Inge replacing it. So we’re putting the battery on a reconditioning program, day and night. Inge takes care of this, along with cleaning up the cockpit from last night, cooking and nursing. It’s already late afternoon when Inge has time to inflate the dinghy. I say: we can do that tomorrow. We leave the Ya comfortably at anchor and Inge and I rest first.

There’s also a small ray of hope: I’m recovering; last night’s adventure hasn’t aggravated my injury. With some extra support from a stiff pillow I can even eat with a spoon now.

Another night with Murphy

I hope, of course, that Inge is getting a good rest. But when the thin crescent moon peeks through the clouds, she sees that cliff from her bunk window as a huge black wall. At night, you can barely see distance, and due to an eye defect already from her youth, Inge also has no good sense of distance. And with the waves, which turn into white, glistening foam on the rocks, it seems even closer. Inge comes to my bunk and says it seems like it’s only a few meters away. What will happen if the wind shifts more?

Has Murphy left?

It went well until morning, although Inge has been up a lot. Still, she feels a bit fresher this morning. She says that during the night, after some rumbling and scraping, she heard a loud “PLOINK” on the anchor chain. Could that heavy thing have slipped off the unmoored anchor? I doubt it, but she’s convinced. Inge checks it, and sure enough, the fore anchor will just lift! That’s a bonus.

The next bonus is that Inge looks fresh. Then a dinghy comes over to us with a French man on board called Jean-Francois. We’re on the stern anchor and that’s noticeable, so he comes to check. How nice. We ask if he wants to help us raise the anchor. Again I eat a lot of Ibuprofen and Paracetamol and I can now manage to cover the two meters from my bunk to the cockpit in just 20 minutes. I do the manoeuvering, and Jean-Francois pulls in the anchor line. Conveniently, he knows what he is doing. Even though it’s a lightweight Fortress, the big thing still weighs 10 kilos with the lead line on it, so we’re glad Jean-Francois is handling the job.

At Jean Francois’s suggestion, we drop the anchor just next to his boat, at only 16 meter depth. We then use the 55 meters of chain we have. I check if it holds, with a firm blow astern. Then I notice we’re reaching 30 meters of water. But the anchor holds and we’re in position.

During our anchoring manoeuver, a dinghy with sailors on board came over to check on us. They also offered to help which was very nice. They knew of a doctor on one of the boats here. They said they’d ask if he could come over. “Great, no rush,” I answered. It’s already afternoon and we’re moored, behind the good old Rocna anchor. We’re relaxing, and this third night we sleep soundly and uninterrupted. Murphy has left – we think!

The Diagnosis

The next morning, the gusts of wind start rolling down the mountain harder and harder. The pilot book warns about this = the gusts often reach 40 to 45 knots.

At eleven o’clock in the morning, the doctor arrives. He is Alain, also French. We explain in our best French what happened, almost a week ago now. He looks and carefully feels. It hurts quite a bit, especially because the gusts are making the boat – and us – sway a bit. I explain in detail the positions I can do, which movements I can make, and he wants to know everything in detail. “And what are our future plans?” he asks in French. Well, now that I’m slowly getting better, I want to go to Nuku Hiva. It is only 160 miles away and there’s a doctor and a small hospital.

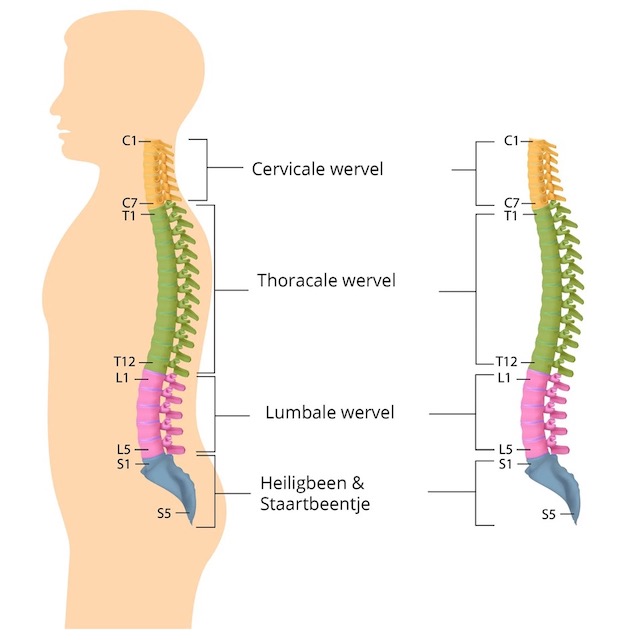

His diagnosis is that the problem isn’t with the (floating) ribs, but just below them. A vertebra may be torn, or even broken. If I were to continue sailing, he said “tu peux finir dans un fauteuil roulant.” The first part means “You can end in”.. but these last words that sound so beautifully from his lips?

Just as I’m beginning to understand that “fauteuil roulant” means ‘wheelchair,’ there’s a lot of knocking on the hull and people shouting loudly and urgently. Inge rushes outside.

Murphy vs Teamwork

“Ton ancre ne tient pas! Your ancre izz not holdinque!” That’s what the French men shout as they climb aboard. Their names are Lionel, Adrien, and his wife, Marine. The Ya is at 60 degrees into the wind and a strong gust makes her heel over considerably. It must be blowing some 40 knots.

The electric anchor winch is unable to pull in the 55 meters of chain – plus the anchor is dragging on the bottom. I tell Inge to stand by the engine handles. There she is centrally located on the boat and can easily pass on my instructions to everyone. Lionel and Adrien quickly know how to get the anchor chain in by hand. We put Marine at the helm. The two men take the chain in meter by meter and when Inge and Marine drive the boat towards the anchor, the chain can easily be pulled in fast.

Then Jean-Luc comes aboard. Also French. He’s a free diver and knows the bay well. He points out an anchorage that’s 20 meters deep and says the ground there is excellent. How much chain do I have? 60 meters, and 50 meters of line behind it. That’s more than enough, then that’s the best spot here, he says. “It’s the only spot,” I think. How difficult this is for me as a skipper, not being able to do anything from your bunk other than follow their advice, so I simply say “Yes.”

So they anchor the Ya there. They put out the 60 meters of chain plus twenty meters of line. Lionel says: “the line won’t touch the bottom then, so it can’t chafe. But it does contribute to leveling the angle.” I gain confidence; these guys know what they’re doing. I ask Inge to give it a full throttle astern. The boat comes to a stop, the anchor holds. That’s not enough for Jean-Luc. He dives for the anchor. He comes back and says it’s deeply buried in the sand.

Evacuation

Meanwhile, Alain has called his medical colleagues in Tahiti. They decide that I must be transported to Nuku Hiva. We don’t know that yet. We were just anchoring when a small fishing boat comes alongside, with a nurse at the front and six men and a stretcher in the middle. Everything happens very quickly. Alain gives me two more large Codeine pills. And I end up on the stretcher. It has a mattress that they inflate. They strap me in and lift the stretcher. With a lot of muscle power, the stretcher goes through the 12 fishermen’s hands.

When I look down, I see water and I think about the buoyancy of the mattress, but I end up in the fishing boat. They take me to the harbor and slide me on to a pickup truck. The fishermen sit on the side of the truck and put a foot on the stretcher to keep me in place while the truck is climbing up a bad road to the pride of the village – the soccer field. The soccer field is the only flat part of the village and there the helicopter can land. Meanwhile Inge has packed all necessary stuff for me and herself and arrives just in time to see the helicopter land.

The anesthesiologist/nurse on the helicopter puts an IV in my arm and gives me something when I feel pain. The fishermen slide me into the helicopter, up we go and Inge has a beautiful view from her seat.

I’m well-drugged when, an hour later, the pilot announces we’re approaching Nuku Hiva and asks me if I can handle it still. “Thank you pilot, I’m fine and I can manage it also a bit longer. So, could you perhaps take a short tour over the island for my wife?” There you go, drugs have the effect to make you think out of the box.

At the hospital the medical team are ready, and within an hour I’m out of the MRI scanner tunnel, and the specialist can give the initial assessment. It turns out I’ve broken a vertebra, so way more serious than a bruised rib.

Fortunately, the loose piece is still in place. So surgery isn’t necessary. But rest and, above all, no sudden movements is necessary. Indeed, sailing 150 miles could have led to a spinal cord injury and a paralyzed lower body. I’m going straight to a hospital bed. They arrange a bed for Inge adjacent to my bed, and the next morning I wake up with chickens under my window.

After two weeks of rehabilitation in Nuku Hiva, I happily return to Fatu Hiva, where the Ya has been moored under Jean-Luc’s watchful eye. I continue my recovery there for another three weeks until I can comfortably hoist the sails again.

The Bad Luck just piled up

After I fell and injured myself, a catalogue of bad luck followed:

- We had a headwind on passage, which is most rare. The steep waves didn’t help my condition and Inge had to work extra hard.

- Instead of making landfall early in the morning as planned, we arrived after dark – so I had to go on deck for the radar observation.

- The bay was full of anchored boats – which rarely happens there. There really wasn’t any good anchoring space left, at least not without thorough local knowledge.

- We picked up a heavy “thing” on the anchor. This caused the anchor to drag. Then it didn’t drop off, rendering the anchor unusable and forcing us to use the second anchor on an extremely long line.

- A shifting wind in the anchorage, to our disadvantage. So it led to two bad nights for Inge, who already had to do all the work on board – from deck work to fixing things, cooking and nursing me.

- A third anchoring attempt on the 15 meter line, that turned out – as the free diver told me afterwards – to be just on the edge of a drop off to deeper water.

- Wind gusts that increased to almost the maximum that can blow there.

Lessons Learnt

What we were grateful for:

- Radar (and my radar observing course). You might only use it once a year, but then you need it. This allowed us to sail into the bay and manouever between the boats, despite the poor visibility.

- Medication: We were grateful for the large supply of ibuprofen and paracetamol we had on board. We were also pleased with the excellent selection of backup medications. It’s a list compiled jointly by the Dutch Kustzeilers and Toerzeilers associations – and they did well.

- Pre-passage planning: We were pleased with our preparations for the passage. For example, the weather forecasts we requested before and during the trip. The directions weren’t entirely accurate, but we knew there wouldn’t be any disruptions or strong winds coming our way, which gave us peace of mind. We were rested and had enough food and beverage with us to be able to sail more slowly or possibly continue to another island or archipelago – although in hindsight, that wasn’t a good idea. Still, it gave us peace of mind.

- Spares: It’s nice to have a spare battery, although we didn’t end up using it in this case. We have a backup of a lot of equipment anyway, and that’s a nice feeling when Murphy comes to visit you.

- Fellow cruisers: We’re very grateful for the ‘mouillage’, the French sailors at the anchorage who helped us in every possible way. We hope they enjoyed the tray of beer Inge gave them in her hurry to get packed.

- Insurance: We had basic medical insurance, but in the end had to pay 500 Euros for our hospital stay. There was no charge for Inge to stay next to me in the hospital – as staff said the hospital was not busy and there was a spare bed. We have still to receive a bill for the helicopter flight!

- The Hospital in Nuku Hiva: The small hospital there has a better MRI machine than Rotterdam! It is full service, well equipped to a very high standard, but any major surgical emergencies must be done in Papeete. I was lucky I did not need surgery.

What can be improved next time?

There was nothing to criticize about the ship or the equipment. Actually, I don’t like an anchor without a chain and this 10 meter of lead line is not much weight. But with Inge’s strength, the lightweight Fortress is already heavy enough. And the lack of resilience due to the lack of a chain can be solved with a lot more line. As long as it’s temporary, because a line can chafe on a rock on the bottom within a few days. The long length of the line is a weak point, due to the enormous swing you can make, and we experienced that first-hand.

What really could have been improved is our communication with the outside world.

- Immediate Radio Medical Advice (RMA): We could have simply requested medical advice after the accident. We considered it as we had basic medical insurance, but didn’t do it. Because we already knew, didn’t we? It was a contusion, we thought. Moreover, after three days there was clear progress, so it was healing, so it’s not necessary, was our reasoning. It must be said, however, that even with an immediate diagnosis of a broken vertebra, I would have followed the same healing path. Still, you have to request an RMA. Those medical people at the other end of the medical insurance line know what to ask and although a proper diagnosis isn’t possible, they can still give you ideas. Perhaps they would have given us the following suggestion, see 2.

- Request Assistance on Approach to Shore: As we approached Fatu Hiva, we could easily have sent a PAN PAN message via the VHF radio Channel 16. Not for medical advice, nor for a tow. But simply for a sailor to come on board and help out. That extra hand would have been a blessing. Someone like Jean-Luc – who already knows the bay – would probably have put us in a better anchoring spot right away. If Murphy were to cause trouble, you could handle it better with a few extra hands and brains. And a fellow sailor is happy to help. We can see that now. Adrien, Alain, Lionel, Jean-Luc, and Marine got Murphy off the boat in three to four hours. But it was night and we didn’t think anyone would have been awake to hear our radio call.

Peter Hoefnagels and Inge van Berkel

SY Ya

Sailing FossilFuelFreeAroundtheWorld

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About the Authors

Peter Hoefnagels is president of the Clean Wave Foundation, skipper of the Ya and the initiator of the fossilfreearoundtheworld campaign.

Together with his partner Inge van Berke, they are sailing around the world without using fossil fuels on board their boat Ya. No diesel, no gas, no petrol. On-board life is energy neutral and very comfortable. Says Inge: “Sustainable cruising means sailing globally, living locally. We buy, eat, live and act where we anchor. With the locals we exchange information and methods about sustainability and living self supporting. Whatever we learn from them, we share with you on our blog. In exchange, we deliver a clean wave in all corners of the globe.”

- See their website: FossilFreeAroundtheWorld for articles on generation and the crucial Energy Balance in set a yacht to be fossil fuel free.

- About their fossil free circumnavigation, see the history section on the website. (If you understand Dutch, then go to www.duurzaamjacht.nl and read all about it)

- Contact SY Ya: info@fossilfreearoundtheworld.org

……………………………………

Other Reports from SY Ya

- Colombia, Cartagena: Noisy and Busy but Charming and Friendly (December 2022)

- Dominican Republic: Coping with the Officialdom of Cruising (November 2022)

- The Gambia: A Great Place for Sailors (January 2022)

- Ya: The Yacht That Sailed the World Fossil Fuel Free

…………………………………

© 2025 Noonsite. This content was edited by Noonsite. Do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of Noonsite.com or World Cruising Club.

If you have found this information useful, become a paid member to enjoy unlimited use of Noonsite plus many other perks. Your membership fees really help our small, dedicated team keep country information up-to-date in support of cruisers worldwide. Find out more about Noonsite Membership levels and benefits here.

Subscribe to our FREE monthly newsletter.

Leave a comment

You must Login or Register to submit comments.