Crossing the Pacific: Planning for The Coconut Milk Run

Having made the case for sailing to the less-traveled corners of the Pacific, north-west and south-east, Francis Hawkings – author of the latest edition of the Pacific Crossing Guide – says there is still great joy to be found on the much-traveled Coconut Milk Run. However, there are also a few special factors about the Pacific that those planning a crossing should know about.

Published 6 months ago

Planning for the Pacific

In two previous Noonsite reports (Taking a Lesser Travelled Path and Discovering What Lies North of the Equator), I have made the case for sailing to the less-traveled corners of the Pacific, north-west and south-east. But there is great joy to be found on the much-traveled Coconut Milk Run route and elsewhere as well. Perhaps uniquely among the oceans of the world, sailing across the Pacific Ocean is mostly a dreamy affair, at least if you are in the middling latitudes. And once you have cast off, there are so many options that your plans can change, endlessly, along the way. There are weather seasons to be respected, to be sure; but within limits, your schedule can be flexible, if you allow it to be, or, even better, forgotten altogether.

But wherever your heart and your boat take you, and as in any ocean, happy cruises are mostly well-planned cruises. Planning is the opposite of tying yourself down: it is about creating options. This is true of preparing your boat, navigation information, medical preparedness, officialdom or many other things. In the main, planning for a Pacific crossing is not radically different from preparing for a North Atlantic circuit or any other long bluewater cruise (spares, spares, spares!). But there are a few special factors about the Pacific that dreamers and planners alike should know.

It’s Big

Obviously, the Pacific is really big. The point from a planning perspective, though, is that the Pacific’s sheer size and the number of nations, islands and continents it contains, gives a cruiser the huge number of options that I talked about at the beginning. Meet many a sailor in the tropics of the Pacific and their plans will prove to be delightfully vague. But it is worth thinking through the boundaries or outer limits of possibility for you: are you likely to want to sail to the cold Pacific as well as the hot? If so, and strange as it may seem when you are in the equatorial heat, should your boat have a cabin heater? Should you be carrying fleeces and blankets as well as shorts and sunhats? Where should you have charts for?

Boats can be retrofitted en route, of course, new gear can be bought mid-cruise and, with a good internet connection, information about somewhere new can easily enough be obtained. But in many places, especially small islands, it isn’t that easy, or cheap, to buy specialized yacht equipment. Few things are more frustrating than waiting for a part to emerge from Customs – and then getting saddled with an unexpectedly large bill.

So to give yourself the flexibility that a true appreciation of the Pacific deserves, it is worth thinking through and preparing for the full range of possibilities you might encounter or want to pursue. Here is a short list that is not necessarily unique to the Pacific, but is particularly relevant to the Pacific (leaving aside generic things like tools, spares, sail-mending materials, etc.):

- Sun awnings

- Good cabin ventilation or even air conditioning; cabin heater for higher latitudes

- Mosquito protection (for example nets to go over hatches)

- Chain rather than rode for anchoring in coral

- Fenders or floats to float the anchor chain in coral

- Big fenders (particularly for Japan)

- Long shore lines (particularly for Chile)

- Flexible propane arrangements to accommodate different fittings and bottle sizes

- Fine-mesh filter funnel for diesel

- Portable water containers (if you don’t have a watermaker) and diesel containers

- Alternative energy generation, especially solar

- AIS: some countries, including New Zealand and the Galapagos, require it (and it is a terrific safety technology in any case).

Officialdom

Bureaucracy – perhaps one of the few not-so-fun things about cruising! When I first sailed across the Pacific – or half the Pacific, to be more precise, because it is so big – you could more or less set off, arrive, and sort out the paperwork once you got there. Not anymore. I recently spent a morning at the Immigration office in a medium-size city in one of my favorite countries. I hadn’t even arrived from a foreign country; I had just sailed into this port’s jurisdiction having been in the country for a year already. All the same, Quarantine, Customs and Immigration all had to come on board or be visited. The boat, my shipmates and I were fully legal, but it took forever to process all the paperwork all the same.

This tightening of regulations has happened especially since two things: the Covid pandemic, which caused countries to want greater control; and the much wider availability of the internet and email on board, which has enabled them to require more information, earlier. The result is that you need to think well ahead before setting off for a new country: what do they require? What advance notice do I need to give? Even if I have not set off yet, what should I do now, while I still have good internet?

It starts with visas (though mercifully this can be done online in many countries now) and in some cases specific permission to visit in advance (for example the Galapagos – or for an arrival at Suwarrow in the Cook Islands). It continues with pre-arrival notifications, often 48 or more hours in advance; then with clearance once you arrive in a new country; and sometimes with intra-country clearances as well, as I just experienced.

There are perhaps two extremes: complex but clear (which would arguably include Australia, New Zealand, the USA, Mexico, the Galapagos (Ecuador) and Japan); and confusing and/or inconsistent (which would arguably include Indonesia, Taiwan and the Philippines).

Complex but clear is preferable; perhaps surprisingly, for example, although Japan has a bad reputation for complex bureaucracy, in practice it is easier to deal with than its confusing and/or inconsistent near-neighbours.

There are also various things you can do to make the process easier. One is to use an agent. Many cruisers do, for example in French Polynesia, Indonesia and Japan; but many cruisers do it themselves in those places too. It really depends on your patience level and budget (though the Galapagos, where agents are mandatory, is an exception). Entry requirements differ from country to country, of course, but there are some documents which you will need over and over again. It is worth carrying spare photocopies as well as the originals, and scanning them to a mobile device as well. Take the whole lot when you go to visit an office, because it is surprising what they will ask for.

For the boat

- Proof of ownership

- Current registration

- Current insurance – many marinas require at least third-party liability coverage

- Clearance papers from the last port of call.

For the crew

- Valid passports for everyone on board, plus visas as needed

- If a crew member is leaving the boat before the boat leaves the country, in many cases it is helpful, or mandatory, to be able to show an airline ticket

- A blank or partially filled out crew list that you can update with full names, dates and places of birth and passport numbers when you reach a new port of entry. The IMO Crew List document is a useful template:

Carrying a printer on board can be very useful for creating documents that the authorities demand. It can also be useful to carry photographs of your boat. Many cruisers have boat ‘business cards’ with their names as well as the boat’s name and details like home port, registration number and radio call sign, plus the skipper’s or owner’s mailing address, phone number and email address. In some countries, for example Indonesia and the Philippines, you may be asked for a ship’s stamp; they typically show the vessel’s name, registration number and home port, plus room for a signature.

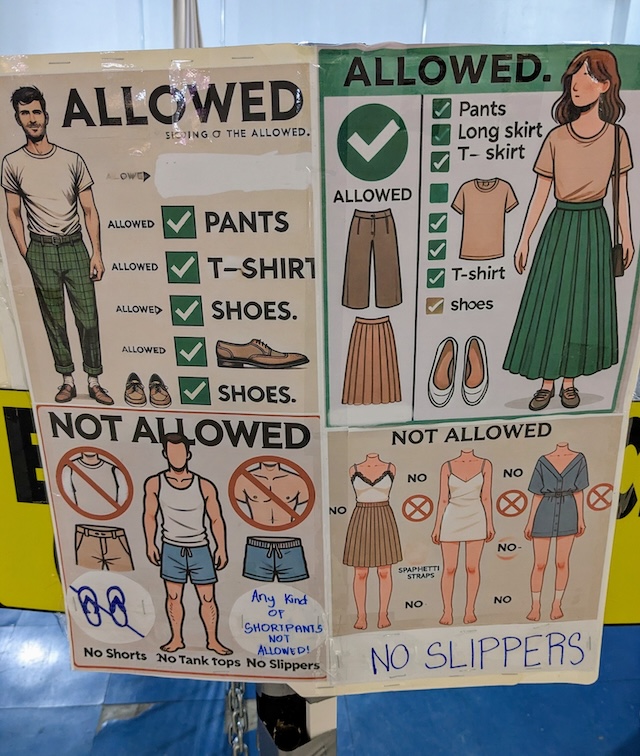

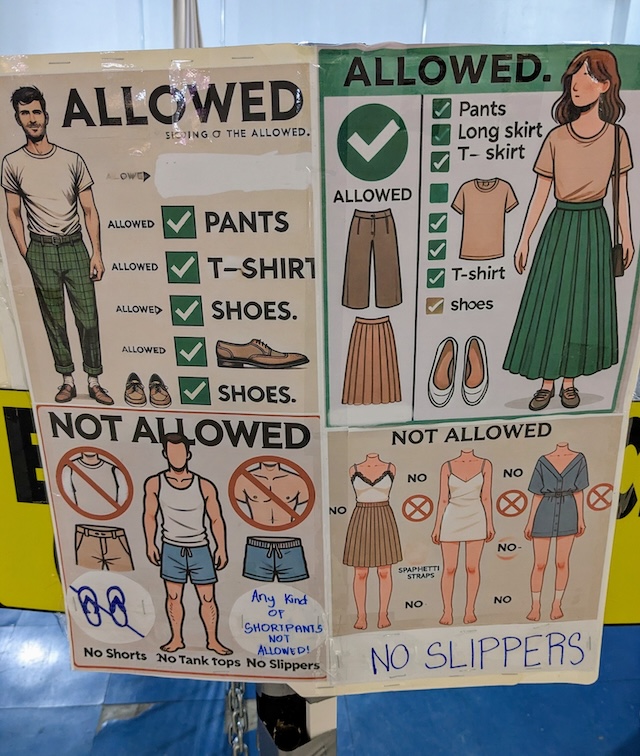

But the best preparation for all this is attitude: expect to spend a lot of time on it; keep it polite and cheerful; make it fun and a cultural experience; and ask for a receipt if a request for a fee seems dodgy. Easier said than done, sometimes; but, ultimately, it’s their country and they are more powerful than you are. Oh, and dress conservatively, just in case.

[Editor’s Note: Noonsite members can gain free access to Noonsite’s Guide to Cruising Paperwork for Foreign Cruising, which covers every single document you might need to have on board when cruising to foreign shores.]

Etiquette

Call me a stickler, but don’t forget to fly the courtesy flag of the country you are visiting! It doesn’t take much effort and it’s a nice gesture of appreciation for the wonderful life we are all able to lead.

Regulatory hotspots and biofouling

In the Pacific, the Galapagos, Australia and New Zealand stand out for the regulatory preparation necessary ahead of time. All three are important waypoints in the Pacific, because the Galapagos are a fascinating stop between Panama and French Polynesia, and both Australia and New Zealand are important havens for those who shuttle between them and the islands of the western Pacific (particularly Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu and New Caledonia) to avoid cyclone season. In addition to the pre-authorization (and use of an agent) required for the Galapagos, all three places have stringent requirements on biofouling. This generally means that you have to clean or have your hull cleaned (and be able to prove that it was done, and when) before you leave the last port before your arrival in these places. The Galapagos and New Zealand both require yachts to transmit on AIS while in their waters.

Australia and New Zealand

The cleaning requirement is within 30 days of arrival in New Zealand, and at your last port or within a week prior to arrival in Australia. They are quite specific about special areas to clean, including around rudders, in onboard saltwater systems (e.g. engine saltwater strainers) and anchors. Boats must also show proof of antifouling (less than 12 months old for Australia; less than six months in some marinas in New Zealand (or lift and wash)).

Australia:

New Zealand:

- Customs – Recreational Vessels and Small Craft

- Biosecurity -Yachts and Other Recreational Vessels

- New Zealand Biosecurity Info. on Noonsite

Galapagos Islands

Biofouling requirements for the Galapagos are similar, along with strict requirements on garbage, fresh food, engine maintenance, detergents, holding tanks and so on.

Galapagos:

- Galapagos Clearance Info. on Noonsite (with helpful 2025 notes from s/v Begonia in the Comments section)

- Galapagos Biosecurity Info. on Noonsite

Food and provisioning

In general, most countries in the Pacific restrict what fresh and sometimes frozen food can be brought into the country, along with firearms, drugs and the amount of alcohol; so be careful what you stock up with, even in the freezer.

The ability to provision varies greatly across the Pacific. In the cities at each end of the Pacific and at major stops like Papeete in Tahiti, shopping is easy and Western brands are common. In between, though, not so much, especially in remoter places like the atolls of the Tuamotus that are resupplied only periodically. The best approach is not to get too attached to one’s favorite foods and to shop like a local; and being flexible is an interesting way to experience the cultures you visit.

Pets

Many cruisers sail with pets, particularly cats and dogs. They are great company but also create complications, because they too have to pass quarantine. Cats are generally simpler than dogs but both mean more planning ahead, proper vaccinations, etc. There is a great deal of information about this on the web; an excellent starting point is James and Jennifer Hamilton’s blog about their circumnavigating cat, Spitfire.

[Editor’s note: Each country on Noonsite has a pet section with details of all the rules and regulations if visiting with your furry friends.]

Communications and technology

In addition to a printer and the ability to scan (even if it is only onto a mobile device), the big technology question for cruisers in the Pacific, as elsewhere, is how to stay connected. Starlink has made fast internet access available at relatively affordable prices and with much smaller hardware, a game-changer compared to the prohibitively expensive satellite broadband systems that preceded it and the painfully slow satellite phone services like Iridium Go, which is adequate for receiving weather, emails and texts, but not for using the internet. Starlink is now rolling out a direct-to-cellphone service, eliminating the need for a dish on board; if and when this is fully developed and widely deployed across the Pacific, it has the potential to be a game-changer.

Although HF radio is still viable, it is increasingly giving way to the different satellite options.

Some starting points:

Navigation and satellite charts

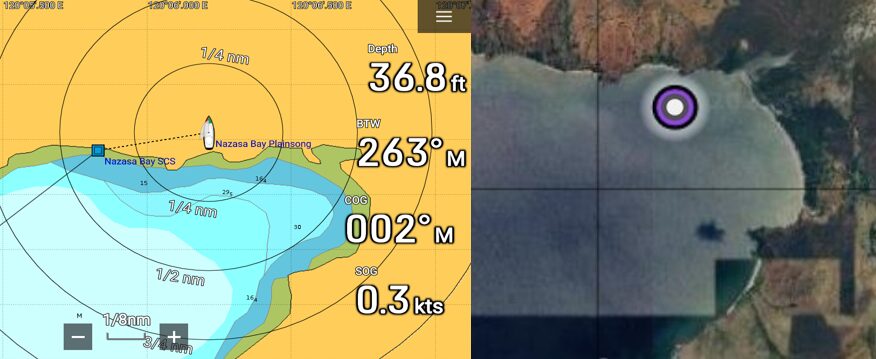

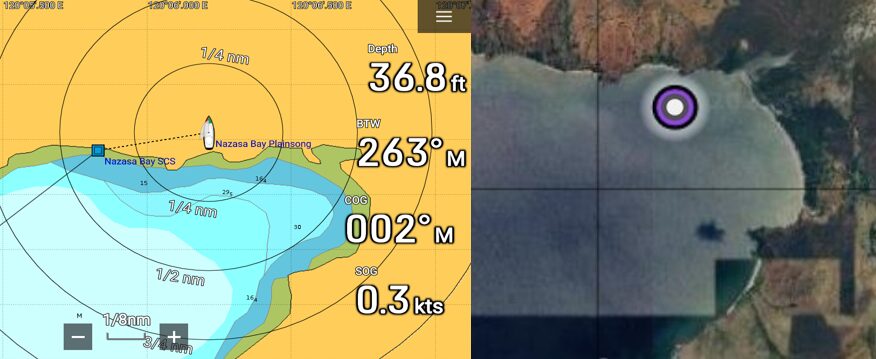

With paper charts now almost a thing of the past, there are many electronic navigation options for the Pacific. Both Navionics and C-MAP have reasonably good coverage, particularly for well-traveled areas, but they cannot be relied upon as the sole source in coral or remote areas. Many cruisers now supplement their charts with satellite imagery, mapped precisely onto OpenCPN or navigation apps like SEAiq or All-in-One Offline Maps. Some cruisers make their own images, taken from satellite sources like Google Earth or Bing, while others rely on the growing libraries of images generously made by other sailors. This is not unique to the Pacific, but the ability to supplement regular charts with satellite images adds a new dimension for navigating in remote areas and is highly recommended for Pacific sailors.

Even satellite images, though, won’t show fish aggregating devices, which are typically unlit, ramshackle bamboo structures or more substantial buoys anchored to the seabed to attract fish, often miles offshore. They can be a significant hazard to sailing at night in the island nations of the western Pacific.

Some starting points:

- Bruce Balan’s Chart Locker

- SV Soggy Paws Charts

- Navigation: How Chart Exchanges Benefit the Cruising Community (Noonsite)

Medicine

Most of the medical best practices are no different in the Pacific than elsewhere. But there are a few things to look out for. Malaria and dengue fever are a risk, mainly in the far western Pacific and particularly Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. Jellyfish, poisonous fish and sea snakes (in some areas), sting rays and sea urchins – all dangers in the water.

Fishing can be fun, and a terrific source of fresh food on passage. But be careful of reef fish (and barracuda): in some parts of the Pacific, ciguatera, a nasty toxin found on coral and seaweed within about 35° of the Equator, can be a risk.

Some starting points:

- Eating Reef Fish and the Risks of Ciguatera (Noonsite Article)

- Medical Kits for Cruising (Noonsite Article)

Information sources and further reading

Jimmy Cornell’s World Cruising Routes has long been the go-to guide for route planning. For the Pacific specifically, the Royal Cruising Club Pilotage Foundation’s Pacific Crossing Guide, recently republished in a 4th Edition by Adlard Coles and from which some of this article is adapted, provides a comprehensive look at preparing a vessel and yourself for a Pacific crossing and contains detailed chapters on the topics in this article and all the major destinations across the Pacific.

Then there are region-specific cruising guides, like Earl Hinz and Jim Howard’s classic Landfalls of Paradise, or excellent guides to Mexico, the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere. Much of the traditional route through the Pacific is well documented with cruisers’ experiences in the Compendiums available through SV Soggy Paws.

Like the ocean itself, though, things are always changing across the many countries and destinations of the Pacific. The most current information, therefore, often lives online, and often in communities and groups. For entry formalities (which change particularly frequently), Noonsite is the most comprehensive country-by-country source that I know of; to check the latest requirements for regulatory hotspots like the Galapagos, or even the regulatory less onerous places, Noonsite is the most likely source to be up to date.

For anchorages and harbours, both Navionics and C-MAP have user-provided information, as do standalone apps like noforeignland and Zulu Offshore (which can also display satellite imagery).

With the spread of affordable broadband at sea, along with regular cellular service when near land, information sharing among cruisers on Facebook and WhatsApp, in particular, has also taken off. There are Facebook groups for French Polynesia, the Western Pacific, South East Asia, the Philippines, Japan and elsewhere and parallel WhatsApp groups for many of these areas too.

Some examples:

French Polynesia:

South Pacific:

Western Pacific:

In fact, it’s almost too much information. One risks drowning in data. It is well worth exploring different sources and apps before you set off and then settling for the few that you feel most comfortable with. After all, the most valuable information is what you discover yourself.

Francis Hawkings

Author

The Pacific Crossing Guide 4th Edition

………………………

About the Author

Francis Hawkings was born in the UK and raised sailing dinghies from a young age, mostly on the West Coast of Scotland. His first cruising boat was a Contessa 26. He has owned his Tradewind 35, Plainsong, since 1992.

Plainsong has been based in the Pacific since 1993 and has cruised extensively in the South and North Pacific, the South Atlantic and the Caribbean. She is now heading generally west to complete a slow circumnavigation and is currently in the Philippines.

Francis is the author of The Pacific Crossing Guide 4th Edition which is available from:

……………………..

Other Reports by Francis Hawkings:

- Article 1: Crossing the Pacific: Taking the Lesser-Travelled Path (South of the Equator)

- Article 2: Crossing the Pacific: Discovering What Lies North of the Equator

……………………..

Related Links:

……………………..

© 2025 Noonsite. This content was edited by Noonsite. Do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of Noonsite.com or World Cruising Club.

If you have found this information useful, become a paid member to enjoy unlimited use of Noonsite plus many other perks. Your membership fees really help our small, dedicated team keep country information up-to-date in support of cruisers worldwide. Find out more about Noonsite Membership levels and benefits here.

Subscribe to our FREE monthly newsletter: https://www.noonsite.com/newsletter/

Related to following destinations: Aitutaki, Ambrym, Anatom Island (Aneityum), Anelcauhat, Apataki, Apia (Upolu), Asanvari Bay, Atiu Island, Australia, Australs, Banks Islands, Bora Bora, Brisbane, Bundaberg, Cairns, Chesterfield Islands, Clipperton Atoll, Coffs Harbour, Cook Islands, Daku Bay, Divers Bay, Ureparapara Island, Eden, Efate, Epi Island, Espiritu Santo, Fakarava, Fatu Hiva, Fiji, Floreana, French Polynesia, Fulaga (Vulaga), Galapagos, Gambiers, Gosford, Hao, Hienghene, Hiva Oa, Huahine, Ile des Pins, Isabela, Kadavu, Kavala Bay, Koumac, Lakeba, Lamen Bay, Lau Group, Lautoka (Vuda Point Marina), Lenakel, Levuka, Lifou Island (We), Lifuka (Ha'apai), Lord Howe Island, Losalava, Gaua island, Luganville, Maewo Island, Makatea, Makemo Atoll, Malekula Island, Mamanucas and Yasawas, Mangareva, Manihi Atoll, Manihiki, Marquesas, Mataura - Tubuai, Matuku, Maupiti, Milli Bay, Mota Lava Island, Moerai - Rurutu, Moorea, Musket Cove, Neiafu (Vava'u), New Caledonia, New South Wales, New Zealand, Newcastle and Port Stephen, Niuafo'ou Island, Niuatoputapu Island, North Island (New Zealand), Northern Group (Cook Islands), Northern Territory (Australia), Noumea, Nuku Hiva, Nuku'alofa (Tongatapu), Off-lying Islands (New Zealand), Oinafa, Olal/Nopul, Other Atolls (French Polynesia), Outer Islands (Galapagos), Ovalau, Pacific Harbour, Palmerston, Papeete, Penrhyn, Port Botany and Kurnell, Port Denarau, Port Kembla / Shellharbour, Port Resolution, Port Sandwich, Port Vila, Puerto Ayora (Academy Bay), Puerto Baquerizo Moreno (Wreck Bay), Puerto Villamil, Pukapuka, Queensland, Raiatea, Raivavae, Rangiroa, Rapa, Rarotonga, Rotuma, Salelologa Harbour (Savai'i Island), Samoa, San Cristobal, Santa Cruz, Savusavu, Society Islands, Sola, Somosomo, South Australia, South Island (New Zealand), South West Bay, Southern Cook Islands, Suva, Suwarrow, Sydney, Tahaa, Tahiti, Tahuata, Tanna, Taravao - Port Phaeton, Tasmania, Taveuni, The Whitsunday Islands, Tikehau Atoll, Tonga, Touho, Tuamotus, Ua Huka, Ua Pou, Vanua Balavu, Vanua Levu, Vanuatu, Velit Bay Plantation (Shark Bay), Viani Bay, Victoria, Viti Levu, Vunisea, Vureas Bay, Vanua Lava Island, Waterfall Bay, Vanua Lava Island, Western Australia, Yamba, Clarence River

Related to the following Cruising Resources: Books, Circumnavigation, Pacific Crossing, Pacific Ocean East, Pacific Ocean North, Pacific Ocean South, Pacific Ocean West, Regional Cruising Guides, Routing

Probably not a great idea to write off HF radio com just yet. The Internet is a candle-in-the-wind technolgy that may become even more compromised as AI advances and becomes more available. Hyper-hacking, spoofing, and fake info will most certainly become mainstream making cyberspace a sketchy resource. Yep, the web is easy right now . . . probably not so much in the very near future. Might be a good time for all ye push-button sailors to actually learn how to navigate, learn how to access HF WX broadcasts/read the weather with an understaning gained from study and experience. Just saying.